The synagogue sanctuary is a single hall with a built-in women’s gallery (ezrat nashim), supported by cast-iron columns decorated with ornamental capitals. Originally, these were colored and the gallery had a mechitzah (a wooden screen that separated the women’s prayer space). As this was an Orthodox synagogue, the bima (an elevated platform for reading the Torah) was placed in the center of the hall and the ark was located on the eastern wall, facing Jerusalem. The ark was accentuated by a large horseshoe-shaped niche and round window above. Traces of blue coloring and an irregular six-pointed star decoration in plaster have been preserved in the niche. As is common for synagogues, tzedakah (charity) boxes were placed on the western wall of sanctuary on both sides of the entrance. The best-preserved feature of the sanctuary is a period wooden cassette ceiling, which was until recently pierced by grain chutes dating from the communist period, when the synagogue was used as granary.

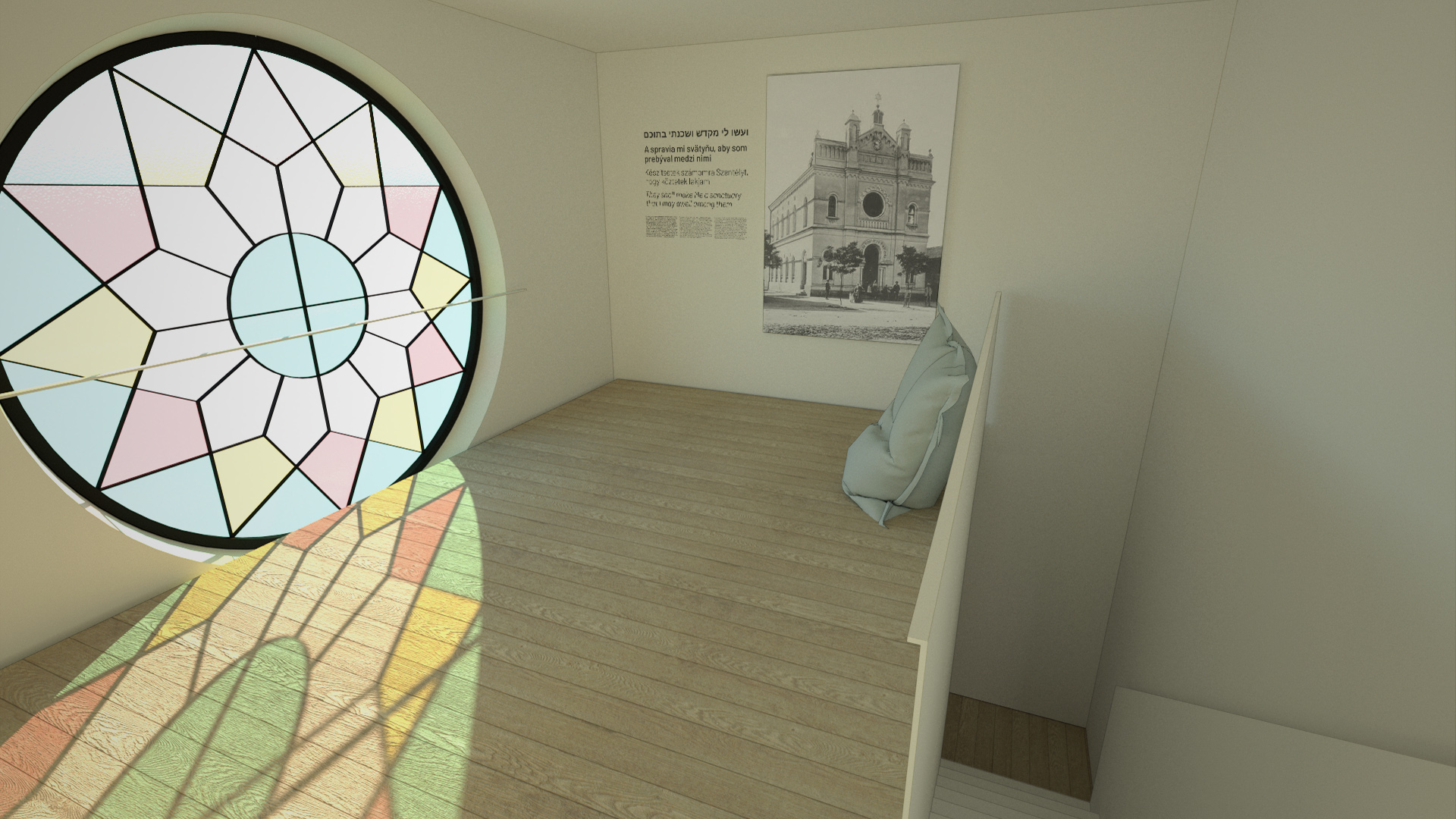

For centuries, since the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple, the synagogue has been the central institution of Jewish life. Referred to as mikdash me’at, a small sanctuary, it in principle substituted for centralized temple ritual including sacrifices. The synagogue is called in Hebrew “beit knesset”, a house of assembly, where the Jewish community meets for regular prayers: three times a day on regular days, and also on Shabbat and Jewish holidays. The Torah scroll is kept in the ark and is taken out and read during the service if a minyan (quorum of ten men) assembles for prayer. Such was also the practice at the Senec synagogue and its entrance portal once featured a Hebrew inscription: “V’asu li mikdash v’shachanti b’tocham / And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8).

The synagogue continued to be used by the Jewish community until the 1950s, when it was confiscated by the communist state and used a granary and storage facility. According to the information we have, the Torah scroll was given placed in the custody of the Jewish Community in Galanta.

In the early 1990s, the abandoned and dilapidated synagogue was returned to the Federation of Jewish Communities of the Slovak Republic. Today, there are no Jewish residents in Senec and therefore no need to use this building for its original purpose. After many years of failed attempts to restore the building for cultural purposes, the former synagogue was purchased for a symbolic one euro by the Bratislava Self-Governing Region. In May 2018, a project to restore the building was launched. After its completion in 2021, the former synagogue will be used as a venue for cultural events. The former women’s gallery will feature a permanent exhibition of Jewish Heritage in the Bratislava Region.